The Sons of the Sea Beggars & the Daughters of Eden

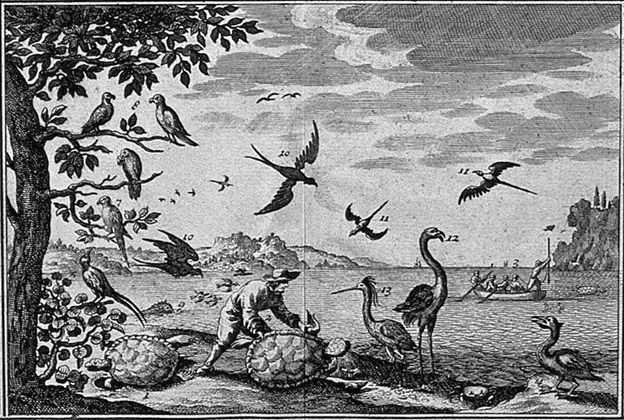

Image: Guedeville’s Atlas, published in Amsterdam by Henri A. Chatelain, 1719

Excerpt for the upcoming book: The Daughters of Eden

Projected release date December 2023

Throughout the 17th century, most new arrivals to the Eastern Caribbean emanated from the old world’s long-suffering peasant and laboring classes. Among them were prisoners of war, condemned criminals, convicted vagrants, penniless orphans, and the destitute poor, all unwillingly transported as a cheap expendable labor force destined to carry out the backbreaking task of carving out the rudiments of colonial infrastructure – the building of forts, wharfs, warehouses, roads, etc. – and the converting of raw land for plantations and settlements. Conspicuous among these outcasts were many hundreds of downtrodden Irish Catholics, who found themselves shipped off to England’s developing sugar colonies to live and toil alongside enslaved Africans and Indigenous-American captives. Others, however, came of their own volition, having signed on as indentured servants or contracted journeymen in the hopes of escaping rural famine, or the pestilence that plagued Europe’s overcrowded urban centers. Most came with high expectations, but only limited skills or resources.

What was to become of theses hapless emigrants? The motley and the maimed, the rogues and ruffians, the youthful dreamers, and hopeful poor. How were they to find a place amidst the simmering colonial-era milieu, with its indiscriminate violence and fractious alliances?

As the modern era dawned over the emerging agro-industrial micro colonies of the Lesser Antilles, the enticing mirage of a New-World Eden rapidly receded from the western horizon, revealing only blood-stained coasts and scarified landscapes shrouded in dust and woodsmoke. For those without wealth or domain, the choices were few. A retreat back to the old world was seldom an actionable response. And so, the path forward most often came down to one of only two unsatisfactory options. Succumb to a short and retched existence under the heels of blunt authority, or join in with the ragged outliers who dwelled upon the region’s remote out-islands, such as Isla Vaca, the Turks and Caicos, Las Tortugas, the towering rock pinnacle known as Saba, or the dry and windswept isles of the Virgins archipelago. Desolate colonial-era backwaters, long-claimed by Spain yet largely ignored, where timbering and the harvesting of guaiacum, salt, copal, and ancient deposits of baleen, along with fishing and the hunting and curing of wild meats, offered a hardscrabble existence on the margins of imperial desires and control.

Indeed, it was in places like these, the flyspec no-man’s-lands with little tillable soil and few valuable commodities, that the Creole sons of the Sea Beggars and daughters of Eden, joined by an ever-increasing cadre of disenfranchised outcasts and their fugitive peers (the so-called ‘maroons’), carved out a niche for themselves. But, while the harvesting of natural resources and the planting of meager provision and cash crops might well have sustained them, freebooting was their true stock-and-trade. And so, while the womenfolk tended to hearth and home, the menfolk set out in search of opportunity. It was a dangerous vocation, deeply rooted in their DNA.